Learning how to draw feet is a skill often neglected in life drawing. However, feet play a vital role in the figure because they ground it, by providing support, and indicating how the figure is balanced. When someone is standing, the feet transfer the weight of the entire body into the floor – a good gesture should run all the way through the figure, through the feet, to the ground.

The most common mistake I see people make with feet is not drawing them! It is all too easy to run out of time and not get around to them, or even worse, chop them off the edge of the paper. To avoid this, it is always worth sketching out the full figure, including where the feet will be placed, at the beginning of the pose. Even a little mark on your paper when you start can be a placeholder for the feet and help prevent them drifting off the paper.

- Seawhites Newsprint paper (opens in new tab)

- Conté Pierre Noir B pencil (opens in new tab)

- Kneaded eraser (opens in new tab)

The foot, has a surprisingly complex structure, which can often make it challenging to draw at unusual angles, or in unusual poses. Like when learning how to draw a hand, understanding of the major shapes making up the foot will go a long way towards drawing it – learning all the bones is great if you want, but isn’t compulsory, as a lot of them are hidden beneath protective cushioning and tendons. (See our how to draw tutorials for more tips on drawing humans.)

The toes are also a common trouble spot, as they are very small relative to the rest of the body – first off, make sure you have the right number! Try to be minimal with the marks you use, and if you can see any shadow underneath them, accentuate it.

01. Use a 'T' shape for foot direction

Even though the foot is a relatively static body part, it does continue on the gesture of the leg – the ankle joint has a lot of mobility! When drawing the full figure, it is good to extend the gesture of the leg through to the foot to ensure it feels ‘connected’ via the ankle. To understand the direction that a foot stood flat on the ground is pointing in, use a ‘T’ that is in line with the heel.

02. Create a wedge

Once I have a good idea of the direction the foot is pointing in, a wedge shape works well as an approximation for the 3D shape of the foot. The base of the wedge should follow the direction the foot is pointing in – often it helps to look at the angle of the side of the foot to place the first edge, and then create a base by drawing across the foot to the other side. Finish the shape by connecting the lines around the top of the foot.

03. Break foot into three

This is an optional step. If you have a foot that is a bit more active – such as this one, which is on tip-toe – it can help to break it into three smaller sections for the heel, the bridge, and the toes. There isn’t much movement between the heel and bridge, but the small block for the toes can bend to match the flexing and extension of the toes. This approach can also assist with feet seen at challenging angles.

04. Focus on the ankle

The foot starts at the ankle, which acts as the connection between it and the lower leg. Here we can see the bones of the lower leg – the tibia and fibula – creating clear bumps on the outer side of the ankle as they create a hinge with the talus. The bump on the outer side of the foot is always lower than the inner side. When seen from the side, the ankle has to be described as a change in the surface of the foot – it has no hard edge.

05. Draw the heel

Most of what we see in the heel is a cushioning pad of flesh that protects the bone from the pressure of the weight of the body, which is why it is a round, soft form. The heel is directly below the ankle, with the Achilles tendon running up the back – this is the line we see in the back view. This tendon is often so thick that it bulges out at the sides, creating a pillar at the back of the foot.

06. Create the bridge of the foot

This area takes up the bulk of the foot. Pay close attention to how the forms are rounded, not flat, and at their narrowest on the outside of the foot before rising up on the inner side above the big toe. I am using directional marks to sculpt this area out, paying attention to the large overall form as opposed to the small details, such as tendons, at this stage. Note how there is a clear edge between the ankle and the bridge, where my marks have changed direction.

07. Outline the big toe

The big toe is essential for us to maintain balance and therefore important to gesture. It is worth being mindful of the rhythm of the gesture running down to the big toe because of this – you get a back and forth flow of rhythm through the leg, down the bridge of the foot, into the big toe and ball of the foot. Don’t forget to make sure that the big toe is larger than the rest of the other toes. Its form can be described by curved hatching wrapping around it.

08. Draw the toes

The first step to drawing the toes is divide up the area they take up to ensure you have the right number – six toes are not an uncommon sight in drawings! This also gives you a chance to get to grips with the proportions of the toes; they all have slightly different sizes. After this lay in, I have worked out the outline of the toes, noting the slight downwards curve to each one. Often, outlining the toes entirely can look clunky, as they interlock quite tightly, so just draw the little shadow shapes between them.

09. Set out little toe

The little toe and the metatarsal behind it juts out a little from the side of the foot. Note how the shape of this toe varies from the others, being less finger-like than the other toes, and instead more rounded. The bridge of the foot is narrowest behind the little toe, and is slightly rounded due to padding, and a small muscle – here I am describing this feature with rounded hatching lines. Behind this, the foot narrows as we approach the heel.

10. Don't forget the toenails

The nails of the toes are very similar to the fingernails in how they curve to fit the shape of the toe. They tend to be somewhat sunken into the form of the toe, with distinctive directions that point inwards to the centreline of the foot. It helps to focus on drawing the toes by implying them with small, broken lines – outlining them entirely will look heavy-handed. On a full figure, you may not even need to include them – if you cannot see them, you don’t need to draw them.

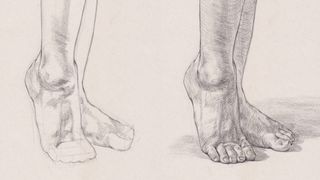

11. Add shadow

In this stage, I am laying in the shadow shapes with a pass of flat tone, focusing on large shapes and making a continuous, even layer of tone by using parallel lines created by the side of the pencil. The near foot is casting a shadow that lands on the other foot, which helps describe the form of the foot, as the shadow shape will fit to the volume. The shadow cast by the figure will extend from the feet, so try to include this, especially on a complete figure drawing, to help ground the figure.

12. Render forms

With the shadow blocked in, I am now focusing on applying more directional marks to describe forms. With the tendons along the top of the foot, be mindful of the direction of your marks – often I find it helps to render them using small marks that go across to show how they create dips and bulges in the surface. This is also a good time to emphasise the directional marks of the hatching on the top versus the side of the foot, and the transition between them.

13. Tighten the linework

Here I am tightening up the linework around the foot. First off, I am looking for areas to push the overlap between lines, such as where the big and little toes fit into the bridge of the foot, and the tendons of the lower leg slot into the ankle. The other thing to look out for is the occlusion shadow where the foot meets the ground, which we can describe using a heavier-weight line. Pay special attention to how this line behaves between the toes.

14. Add finishing touches

Work over the foot as a whole to capture the last few details, such as areas where the skin is creasing, subtle bumps in the contour, such as the back of the heel, and other small details. Resist the urge to overwork things, especially on the light areas, as too much rendering will make them look unnaturally dark. This is also a good time to adjust the edges of the shadow areas.

This article originally appeared in Paint & Draw: Anatomy. Buy the bookazine from Magazines Direct (opens in new tab).